“…seen from the opposite side of the river, they appear like three alcoves. We name this Trin-Alcove Bend. Going up the little stream in the central cove, we pass between high walls of sandstone, and wind about in glens. Springs gush from the rocks at the foot of walls…”

A view of Trin-Alcove Canyon from across the Green River. Photo credit: Yaro Severn

Following the water upstream in Trin-Alcove Canyon. Photo credit: Todd Tompkins

Standing here in Trin-Alcove Canyon on a clear moonlit-night, in the footsteps of this intrepid explorer over a century and a half later, I listened to that sweet little stream draining fresh spring water into the Green River. “Follow me! Follow me!” The endless stream of molecules play a game of telephone. Hardly does the message leave one to be passed upstream, than the next molecule is there to pass the message again. “Remember last time we were here?” they ask each other as they make their way busily past some stones in their path. “The walls weren’t so high then!” “Yes, yes!” “That cottonwood wasn’t there last time.” “We are headed to sea,” they recall. Sadly, I softly tell them “I’m sorry, it’s not likely. Times have changed”.

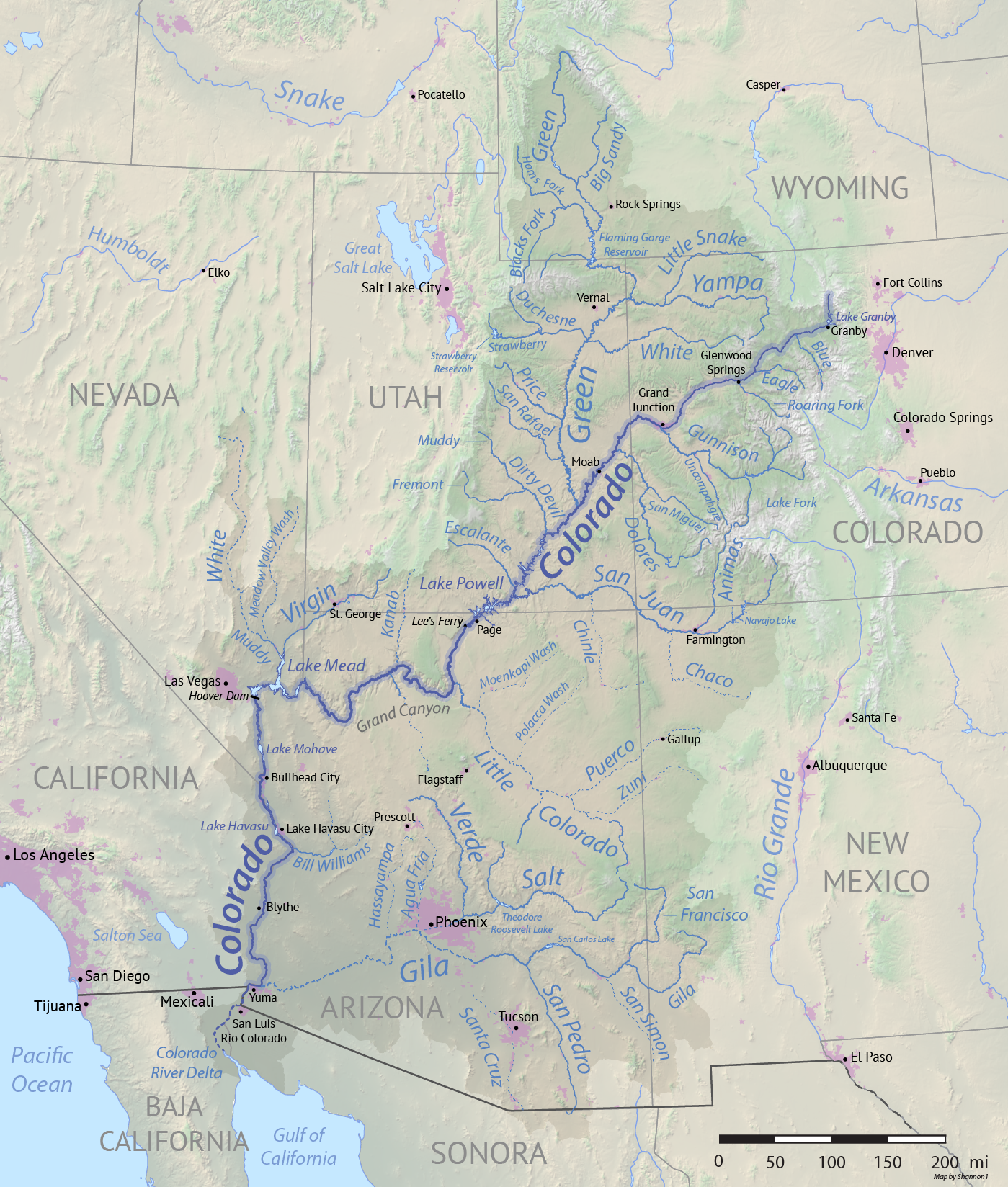

When Powell first explored this canyon, the natural flow of the Green River, as it met the mighty Colorado, ran through the Grand Canyon and many hundreds of miles later, after traveling past numerous Native American settlements, it culminated in a great delta at the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California). Before Powell navigated this part of the river, at least two distinct ages of Native Americans had peopled this region: the Archaic people whose mysterious art marks their presence 4,000 years ago and the Fremont people about 1,000 years ago. Passing further back through time, we would see Trin-Alcove Canyon’s bottom rise as the stream’s erosive effects move in reverse. These water molecules have surely been here before.

The journey of the Colorado River

Fast forward from Powell’s salient footsteps to mine and we would watch the rivers that join to form the Colorado River, from the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming and the central Rocky Mountains in Colorado be dammed, channelized, polluted and diverted as its waters reach lawns in Phoenix, fountains in Las Vegas, parks in Los Angeles, and faucets in San Diego. As of 1960 these waters no longer reached the Sea of Cortez. A once lush delta which was home to multitudes of species of birds, fish, mammals, and plant life disappeared. The human toll of this watershed destruction is evident in not only the downfall of farmers who subsisted in these areas of Mexico but also numerous Native American Tribes in the United States who are fighting to regain their rights to any of this water.

The Colorado River as it disappears into the sand without joining the Sea of Cortez.

The mighty sandstone cliffs bordering the section of the Green River I canoed down have worn down over the millennia, and have become the sand dunes of Gran Desierto de Altar in Sonora, Mexico, carried by the flow of the Colorado. This mingling of fresh water, sediment, and nutrients from our inland regions with the sea is a critical aspect of biodiversity. But when we focus on water supply alone for our inland populations, we ignore the consequences of our actions on ecology. Although the story is much more complicated than this, in 2014 the U.S. and Mexico reached an agreement to release annual “pulse flows” of water from the Morelos Dam, timing it to achieve the prime habitat gain with tree/plant germination. Briefly, the flow of the Colorado reunited with the Sea of Cortez in what some hope will be the beginning of a revitalization of this region. This flow is still only about 1% of the original volume this region historically experienced. It’s a small step toward hope, but not anything close to a repair of decades of degradation.

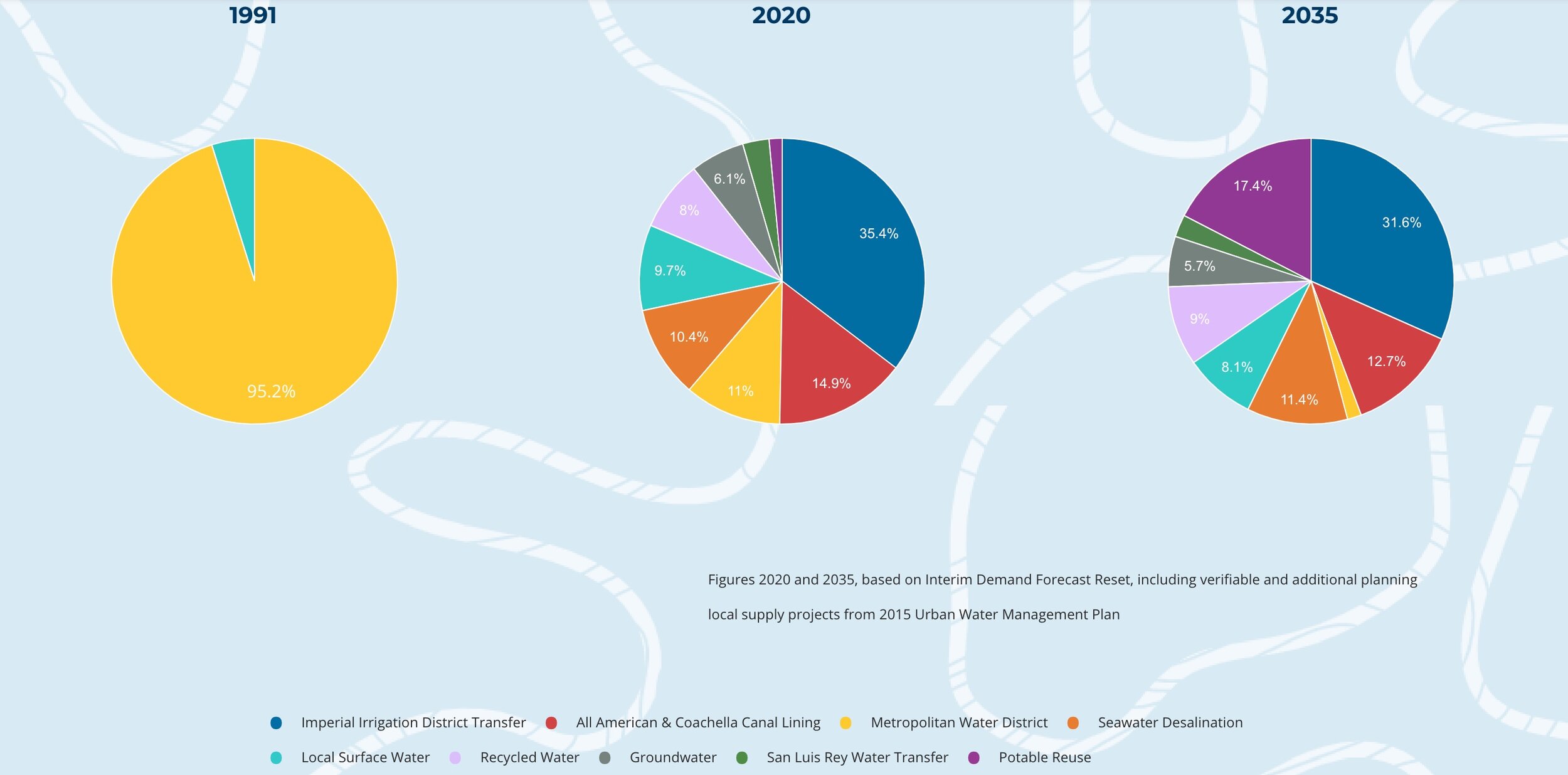

San Diego first began to rely on imported water supply in 1946. Though engineers had began considering and working toward bringing Colorado River water to San Diego since the 1920’s, it wasn’t until World War II ramped up when our population swelled with military personnel and industry that Colorado River Water started to fill our resevoirs. By 1991 San Diego was almost completely reliant on the deliveries from the Colorado River Aqueduct and the State Water Project from Metropolitan Water District. Since then, our local water managers have diversified our water supply portfolio, recognizing how risky it was to rely almost exclusively on water imported from hundreds of miles away, especially in light of the extreme litigation over Colorado River allocations and drought conditions throughout the west.

Although the San Diego County Water Authority appears to be diversifying as seen in the charts below, keep in mind that although the yellow portion (Metropolitan Water deliveries from Colorado and the Bay Delta) has shrunk to 11% in 2020, down from 95.2% in 1991, the largest chunk of our water supply today is 35.4″% from Imperial Irrigation District. That’s ALL Colorado River water, diverted to Imperial Valley!

Source: San Diego County Water Authority

In 1900, some entrepreneurs decided that the Imperial Valley could really be something if it just had water, so they hired an engineer to create the Alamo canal which split off some of the flow of the Colorado River, pouring water into the Imperial Valley. In 1905, a flash flood ripped through the area and the whole Colorado River changed course into the Alamo canal creating the Salton Sea. It took years, millions of dollars, and a lot of engineering to restore the flow of the Colorado River. But the Imperial Valley remains, and is a great beneficiary of Colorado River water at reduced agriculture prices. They in turn sell their water to San Diego, not only in the form of water allocations, but in the form of produce on the shelf.

The red, 14.9% All American and Coachella Canal Lining portion of the 2020 graph is a “conservation” project designed to deliver Colorado River water more efficiently without losses due to water soaking in along the way. So all of this adds up to San Diego still relying on over 61% imported water supplies, largely from the Colorado River.

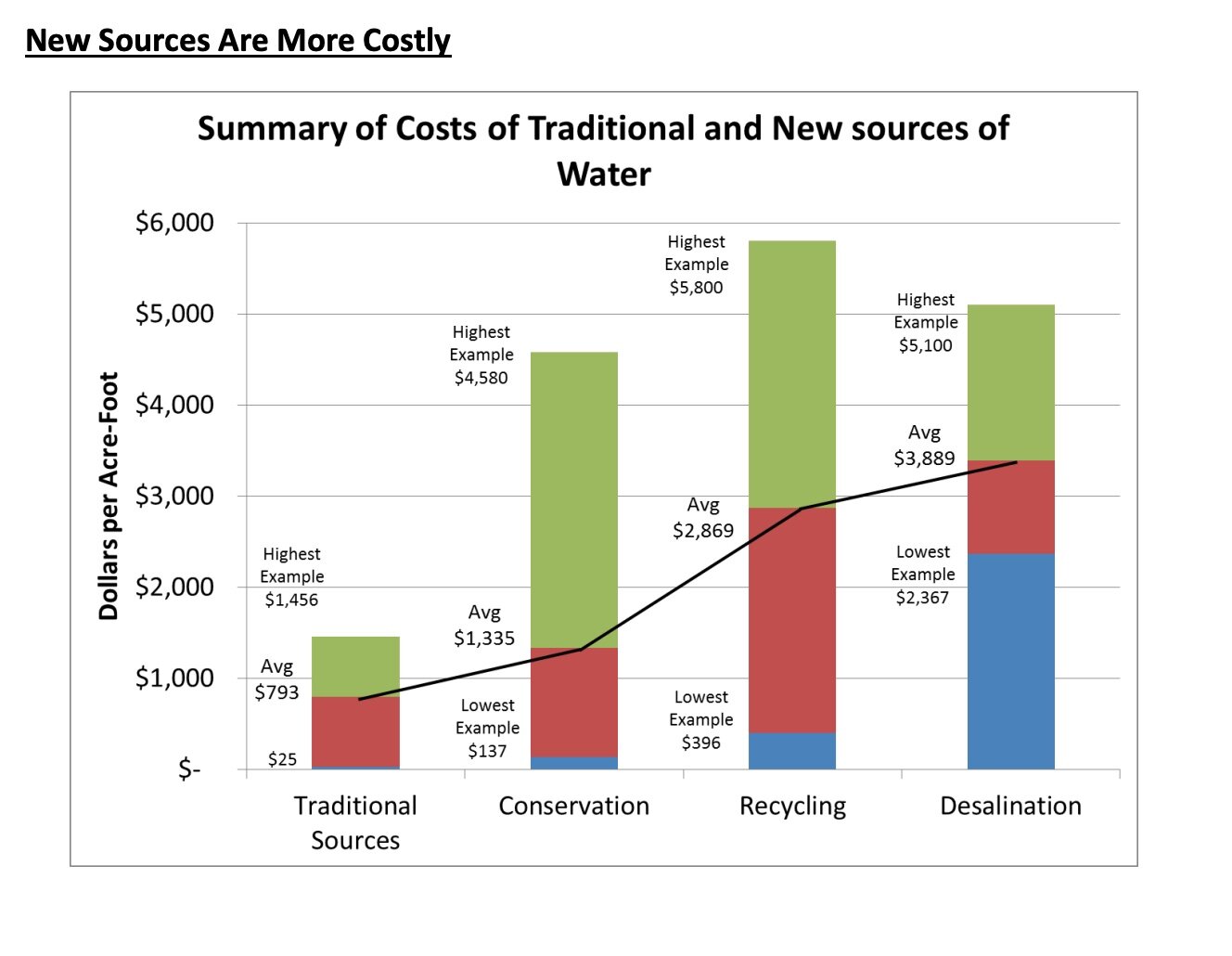

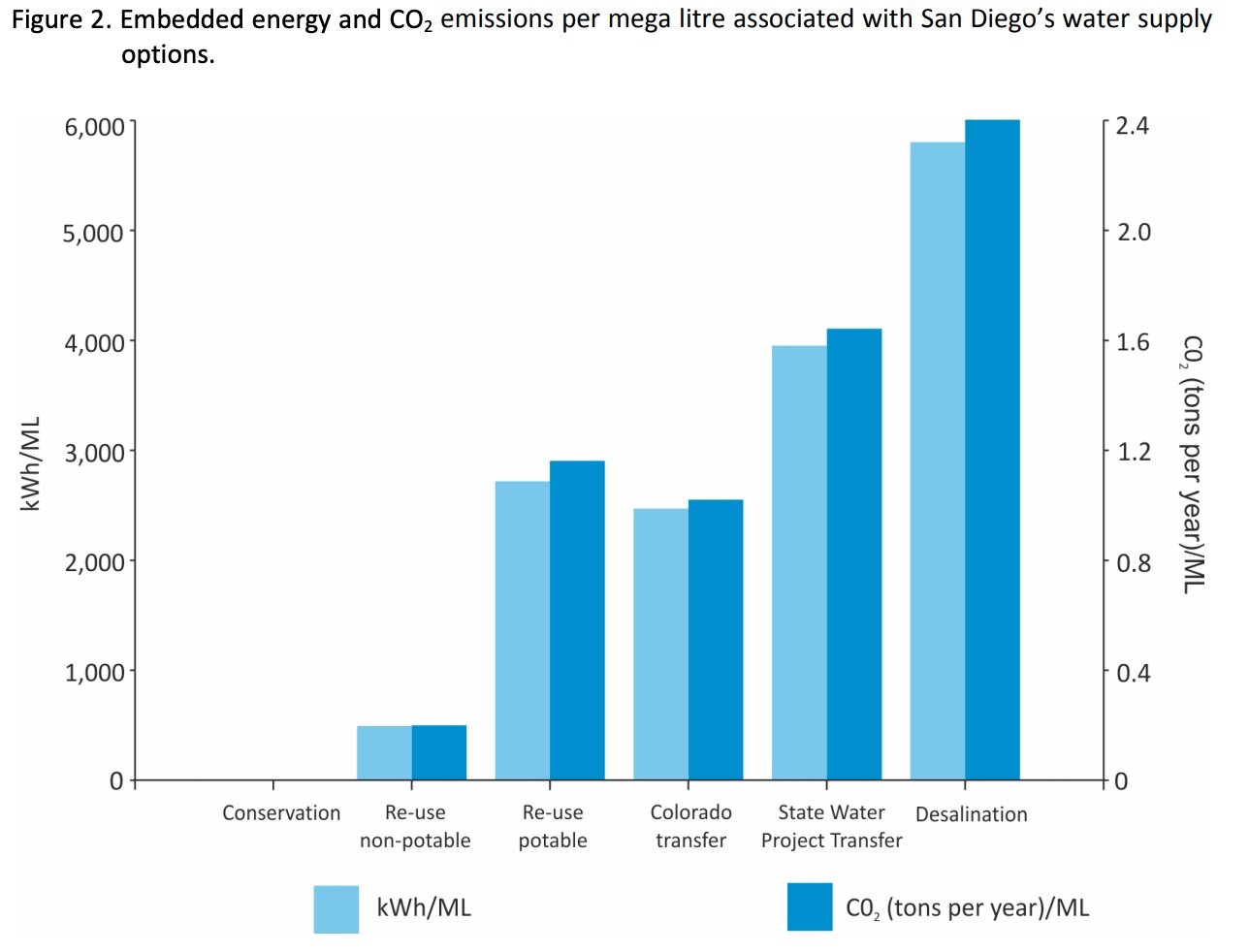

Aside from imported water, much of the remainder of our water supply comes at high cost, financially as well as resulting in carbon emissions. Potable reuse is the most promising long term investment, but it is extremely expensive and desalination is not only ecologically deplorable, but it is the most expensive option we are currently using. Recycled water, or purple pipes, is not quite as expensive as potable reuse and desalination, but because of how it is implemented, it is not widely available to most development opportunities.

If we had to rely on our local water supplies, surface flow and groundwater, we’d have to face some hard realities about living in this region. Choices about watering expensive landscapes, swimming in chlorinated pools in our backyard, driving across the county daily for commuting or recreation, and picking up vegetable grown in the Imperial Valley on Colorado River Water might be more calculated. We should be holding our water agencies responsible to help us make good choices to support each other with our limited resources rather than expect our water agencies to keep upping supply as we go about our business in ignorance to our limited resources. Conservation, as a water supply option, costs the least amount of money. When we start talking about using our local resources to create healthy soil and grow biodiversity in our urban environments using greywater and rainwater harvesting practices, conservation can actually lead to Carbon Sequestration!

This is why we at CatchingH2O work so hard every day to help our community understand how to better value the water we are using by making EVERY DROP COUNT! A drop of water in your shower has travelled so far to get to you, at such great expense. Use it twice! Grow a fruit tree with it. Water that falls from the sky is shunted out to sea by the hardscaping we replaced native vegetation and soil biology with. Do everything you can to keep that water that falls on your roof and in your yard from heading out to sea before you’ve given it a chance to hydrate our soils and grow us shade, habitat, and food.

5000 gallon tank in Carlsbad, along with whole house greywater installed by CatchingH2O. Landscape designed and installed by Ecology Artisans.